removal of bluestone reef at the falls

– see Fri 22 June 1883 ‘The New Princes Bridge’ —-trove

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/120728236?searchTerm=the%20new%20princes%20bridge

also

25

exAMPLERFREFI

50 PARArfergergertighweirghqierhugqeirgqeirghierghiqeurhgieurghiurehgqieruhgqierughiqeurhgiquerhgiquerhghqieruhgqieurghiqerhgqierugh

25

SOURCES AWEFHBAERFHQBERFHB

table > transform to stripes for rows instead of columns showing

| Wefwefaerferfgqergaergqergqerg | qergqergqergqergqergqergqergqergqergqergqerg | qergqergqergqergqergqergqergqrgqergqergqergqergger |

guguyguyguyguyguyguguguyguguoyguyguguyguyuyguyguguyguguygouyguoyguyguyguyguyguoguyguguyuyguyuyguyguguyguyguv

vjhghf

| ‘DIGGING HOLES IN MELBOURNE’ By Jenny Brown October 16, 2017 http://www.domain.com.au/news/digging-holes-in-melbourne-20140822-1078gu Behind a fringe of trees on the Heidelberg-Warrandyte Road at Templestowe is a hole that is so big, it makes the bulldozers pushing dirt around at the bottom appear toy-scale. For 40 years, until the deepest stratum of bluestone was worked out in 2002, it was one of the last of the once numerous metropolitan rock quarries. Now known as Manningham Quarry, it is progressively being rehabilitated – that is, partially filled up – by operating as a receiving depot for clean fill excavation dirt from Eastern suburbs building projects. Already the back-fill has lifted the level in the crater by about 35 metres. It will take another seven years to make a surface that might become a level playing field or a public open space. While hard rubbish and suburban garbage has been the usual refill matter, the redeployment of big holes as dumps is what has generally happened to the pits we have been gouging like gophers into the Melbourne landscape since the 1830s. We flattened Port Melbourne’s sand-dunes for brick sand (and returned night soil – or human manure). We pocked the Southbank claypan for very poor brick clay. (The bricks disintegrated). We pulled 100 years of bluestone out of the Collingwood Quarry that is now Clifton Hill’s Quarries Park. (It was refilled with garbage). We made the only real island on the Yarra, Herring Island, when the bluestone wall of Richmond Quarry was breached in 1928. Hawthorn had high quality clay and the recycled, speckled Hawthorn bricks are still in high demand. Geelong, the Mornington Peninsula and Lilydale provided the lime. The Sandbelt’s ancient dune system that stretches from Cheltenham to Frankston and inland to Clayton, was dug up for builder’s sand. In the 1890s, 15-20 cartloads of sand were daily being dispatched from around Clayton. While the Diamond Creek and St Andrew’s area is still a subterranean Swiss cheese with some 225 old goldmines – some hundreds of metres deep, no landscape was more exploited than the inner northern suburbs of Brunswick, Northcote and Coburg. The last was a suburb originally known as Pentridge until the rock-breaking hard labours of the inmates of “Bluestone College”, or Pentridge Prison, gave it too dishonourable an association. Coburg, the name of a Royal lineage, was the classy rechristening. Northcote and Brunswick had terrific clay underfoot. By the early 1860s there were 50 brickyards, with the Hoffman’s outfit employing up to 800 people. By 1865, most of the labourers in the district were working either in brick making, pottery and tile-making, or as quarrymen. By 1875 there were 41 quarries in the creek corridor. With the Merri Creek in some places having basalt cliff exposures of 20 metres, there were points where bluestone extraction was relatively easy. In other places, such as the Wales Quarry near Albert Street, Brunswick, the digging went way deep. Over the 100 years that it operated as Victoria’s biggest road stone gravel producer, the Wales operation went down to 51.8 metres. When the quarry closed in the 1960s, it was taken over by Whelan the Wrecker. The backfill that went into the gigantic wound came from beautiful Victorian buildings on Collins Street and the early industrial factories, the firm was so busily demolishing. A lot of the red-brick fill that packed the hole beneath the turf of Phillips Reserve had probably emerged from proximate ground as squishy clay. It’s an extreme example of the recycling of building material. Old Wales Quarry site Melways map 30, B8. SOURCE: http://www.domain.com.au/news/digging-holes-in-melbourne-20140822-1078gu |

and

https://citycollection.melbourne.vic.gov.au/princes-bridge-in-1883/

and this is for Falls Bridge then later Queens Bridge

https://www.facebook.com/Past2Present1/photos/a.646640142031892/1546756142020283/?type=3

and princes bridge early pic

https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE1140186&mode=browse

1863 photo:

https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE390512&mode=browse

1880 photo:

and

https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/yarra/taming-the-river/

bluestone history

Early Discovery and Use of Victorian Bluestone

Miles Lewis has previously established 1845 as a likely date from which bluestone was

used in Victoria.1

In addition to his cited evidence, further confirmation can be found.

New South Wales was importing a ‘hard blue stone from Tasmania in 1836 and 1841,

suggesting none was available from Victoria.

2 The first contemporary reports of the use

of bluestone in Victoria appear in 1845. Sydney’s Morning Chronicle stated in January

1845 that Melbourne had quarries of a blue whinstone (q.v.) on the Merri Creek and this

stone was to be used in a bridge.3 Described as being nearly blue-black in colour and

available in ample supply, the stone broke well, and large blocks could be obtained.

Days later the same paper informed readers that the new Government Offices in Port

Phillip would be constructed with the ‘handsome blue-stone’.4

Alexander Sutherland linked the discovery of this bluestone by 1845 to the establishment

of a flour mill at Dight’s falls on the Yarra.5 Sutherland also attributed the early use of

bluestone to Jonathan Lilley, later of Yarraville, who supplied stone for the first Prince’s

Bridge, a bluestone house erected in Melbourne for Dr. Howitt and pitchers for Elizabeth1 Miles Lewis, “3.07.6 Earth and Stone: Stones 2013,” Australian Building: A Cultural Investigation, 2013,

accessed May 6, 2013, http://www.mileslewis.net/australian-building/pdf/03-earth-stone/3.07 stones.pdf.

2

“The Revenue,” Sydney Herald, July 3, 1837, 3; “Memorandum Respecting the Capabilities of New

South Wales,” Sydney Herald, April 15, 1841, 2.

3

“Port Phillip Extracts,” Morning Chronicle (Sydney), January 1, 1845, 4.

4

“Port Phillip,” Morning Chronicle (Sydney), January 18, 1845, 3.

5 Alexander Sutherland, ed., Victoria and its Metropolis: Past and Present, Volume 1 (Melbourne:

McCarron, Bird & Co. Publishers, 1888): 202.

185

street.

6 This dual use of bluestone for building and the management of roads and water

is also exemplified by the Port Phillip Government requesting tenders in 1846 for the

supply of bluestone, ‘fit for Ashlers, for the Fresh Water Dam at Melbourne’.7 An

insufficient supply of granite for the construction of the original Prince’s bridge over the

Yarra in Melbourne between 1846 and 1847 triggered the search for further sources of

bluestone which could be delivered either by land or by water.8 SOURCE: Malmsbury Bluestone and Quarries:

Finding Holes in History and Heritage

Susan M. Walter

Bachelor of Agricultural Science (Hons.) (La Trobe University) pp104-105

A horse-drawn railway to

Pentridge (Coburg) through the bluestone quarries was proposed in September 1853 to

assist the cartage of stone for building purposes, and a branch to the Collingwood

stockade envisaged.

27 Within weeks, a Melbourne correspondent to the Sydney Morning

Herald was bemoaning the enormous cost of building with bluestone when compared to

the ‘permanent and intrinsic value of the erections’ but also the absence of ‘railways,

canals, docks’ making Melbourne both the ‘richest and the poorest of cities’ at the same

time.28 SOURCE: Malmsbury Bluestone and Quarries:

Finding Holes in History and Heritage

Susan M. Walter

Bachelor of Agricultural Science (Hons.) (La Trobe University) p-187

The construction of the Treasury building in Melbourne was said to be the circumstance

under which mechanical stone-sawing commenced in Victoria.63 John Danks was later

credited with making and erecting ‘all the machinery for Mr Huckson, including the first

stone-sawing machine in the colony’; Robert Huckson, being the contractor for the

works.64 There is no evidence that Danks ever patented this machine, implying it was

either a design brought in from elsewhere or not of sufficient rigour to justify more than a

single use, and there appears to have been very little interest in this in the local media.65

Historian Stuart McIntyre asserts that the content of publications like Victoria and Its

Metropolis (1888), may have been contributed by those who featured in it and subscribed

63 James Smith, ed., Cyclopedia of Victoria Volume 1 (Melbourne: The Cyclopedia Company,1903), 353.

64

“Contracts Accepted,” Victoria Government Gazette, December 31, 1857, 2581.

65 A search of Trove and OCR digital version of Government Gazettes using combinations of one or more

of the words Danks, Huckson, stone, treasury, and saw resulted in no reference to this sawing machine.

Figure 41: James Tulloch’s machinery to Saw Grooves and Make Mouldings

on Marble and other stones

Source: Holtzapffel, Turning and Mechanical Manipulation, 1203.

196

to the publication.

66 It is interesting to note that the stone saw is not mentioned in the

article on John Danks and Son in the Victoria and Its Metropolis, when Danks was alive

but it appears in The Cyclopedia of Victoria, published a year after John Danks’s death

and nearly 50 years after these events had taken place, potentially with few pioneers left

to argue over facts.67

Lewis states that ‘in 1862 all stone sawing in the colony was again being done by hand’

and cites Mayes as stating, ‘although the cost of mechanical sawing was in theory only

about one third that of hand sawing, the demand was not enough … to justify the use of

machinery’.68 This is partly taken out of context. Mayes does not state that there was no

mechanical sawing in the colony of Victoria, instead he demonstrated the economies of

scale inhibited the broader used of such machinery at that early stage of the stonesawing industry.

69 Thus, in 1862 at current levels of stone demand, it remained cheaper

to saw with manual labour which in turn, using the basic economic principals, drove the

demand for manual sawing….

While there is a record of a machine being used to plane or dress bluestone in 1861, it is

not until 1865 that any strong history on sawing bluestone in Victoria can be

established.7

p195-196-197 SOURCE: Malmsbury Bluestone and Quarries:

Finding Holes in History and Heritage

Susan M. Walter

Bachelor of Agricultural Science (Hons.) (La Trobe University)

The United Operative Masons formed

in Melbourne in late 1850 having a membership of over 100 within the first three

months.83 At a dinner held at the Royal Exchange Hotel in February 1851, they made

their toast to the success of bluestone, believing that despite it being a hard stone to

work, it could be ‘the making of many a mason in the province of Victoria’.

84 Masons

James Stephens who arrived in Melbourne in 1853, and James Gilvray Galloway who

had arrived in 1855, are given due credited for their role in forming the Collingwood

branch of the Society in February 1856 and the introduction of the Eight Hours

Movement several weeks later.85 —p199 SOURCE: Malmsbury Bluestone and Quarries:

Finding Holes in History and Heritage

Susan M. Walter

Bachelor of Agricultural Science (Hons.) (La Trobe University)

PRINCES BRIDGE

Case Study 3: Munro versus Richey – Burning Bridges pp352-357

SOURCE: Malmsbury Bluestone and Quarries:

Finding Holes in History and Heritage

Susan M. Walter

Bachelor of Agricultural Science (Hons.) (La Trobe University)

rundown on local journals in 1850s see p 357 The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1851-1861 by Geoffrey Serle, 1977 Melbourne University Press.

history of australian buttons omg https://www.austbuttonhistory.com/

Craig, Williamson’s Elizabeth Street store c1890. (Source: Craig, Williamson Draper and Frank L Carr Jr

c1890, SLV)

Age 13 February 1899 p1

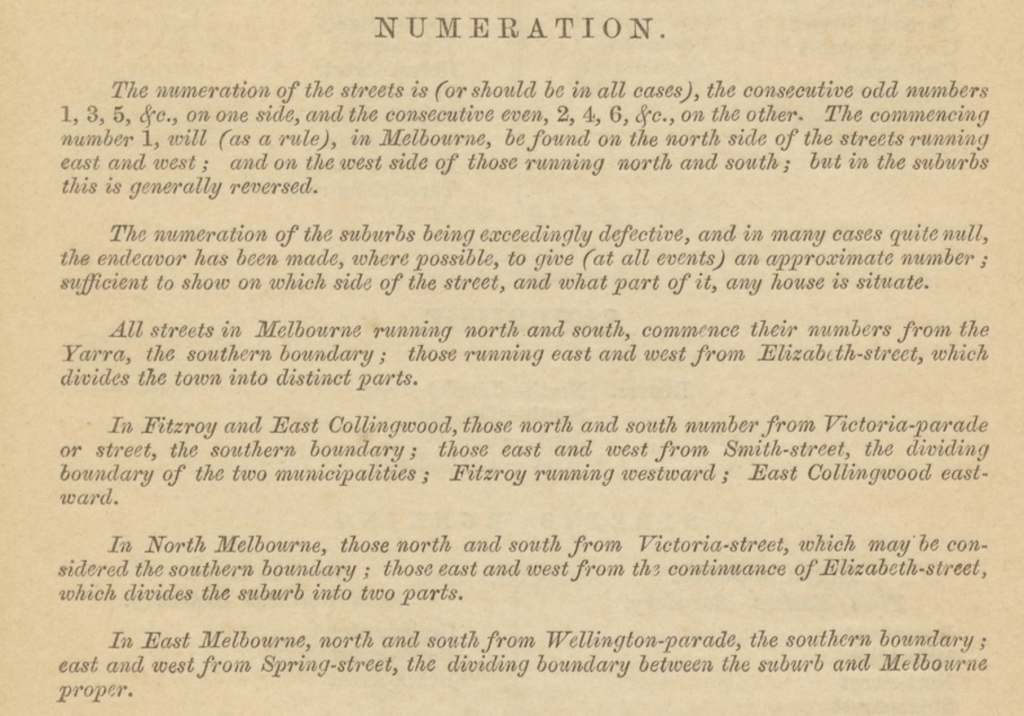

NOTE ELIZABETH ST is taken as the dividing line between east and west of the street according to p.25 1860 Sands, Kenny & Co.’s commercial and general Melbourne directory for … : 1860 Melbourne : Sands, Kenny & Co. 1860

-unsure about north and south.

see this page 26:

1860 Sands, Kenny & Co.’s commercial and general Melbourne directory for … : 1860 Melbourne : Sands, Kenny & Co. 1860

https://mhnsw.au/collection-strengths

TO DO LIST

https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/finding-the-hidden-hellenism-in-melbourne

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/HwWxwNfUzxgA8A

https://www.docklandsnews.com.au/the-citys-light-source/

hist of bourke st:

The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957) Sat 23 Jun 1934 Page 4 THE STORY OF BOURKE STREET

the timeline in this article feels wrong and confuses me

https://www.cbdnews.com.au/old-melbourne-law-court/#:~:text=This%20unpretentious%20wooden%20building%20with,earliest%20public%20buildings%20in%20Melbourne.

further reading J. Armstrong, ‘History of Prisons in Victoria’. The Bridge, Vol. 3, No . 4, May 1980. p.4: The Old

Melbourne Gaol. Text by Robyn Riddett & Geoffrey Down. Melbourne, National Trust of Australia

(Victoria), 1991. ppA-5.

SITES

https://aboriginal-map.melbourne.vic.gov.au

https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au

STREET DIRECTORIES

The closest thing to street directories 1836-1839

Port Phillip District householders were first listed in the censuses of 1836 and 1838, and in the 1839 post office directory, all issued in Sydney.

-Directories https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00470b.htm

1841

the first list of some 900 Melbourne individual and business names was contained in Kerr’s Melbourne Almanac, and Port Phillip Directory, for 1841, compiled by William Kerr (1812-59), then editor of the morning newspaper The Port Phillip Gazette and Melbourne Advertiser. (This directory was reprinted in facsimile in 1978.)

A second edition in 1842 contained 1944 names. Two short directories were issued by the Separation Association in 1845 and 1846, under the title Port Phillip Separation Merchants’ and Settlers’ Almanac, Diary and Melbourne Directory/Directory for Melbourne. Two years later The Port Phillip Almanac and Directory, for 1847, compiled by J.J. Mouritz, was issued by the Port Phillip Patriot (reissued in facsimile, 1979) and also by the Port Phillip Herald. Mouritz’ Directory For the Town, and District of Port Phillip contains upward of 4500 names. Although Mouritz left register books at various business places for readers to supply additional names and corrections for future editions, no more seem to have appeared.

Melbourne in the gold rushes saw an explosion of directory publishing: the Victorian Directory (1851), the New Quarterly Melbourne Directory (1853); The Melbourne Commercial Directory compiled by P.W. Pierce (1853); several Melbourne commercial directories between 1853 and 1856; and (John) Tanner’s Melbourne Directory for 1859. Copies of these are now quite rare, for all were short-lived compared with the series of annual commercial and general directories of Melbourne and suburbs inaugurated by John Sands of Sydney in 1857. These appeared first as Sands & Kenny’s directory (1857-59), then as Sands, Kenny & Co.’s directory (1860-61) and finally as the long-enduring Sands & McDougall’s directory. Dugald McDougall (1834-85) joined Sands & Kenny as Melbourne manager in 1860, became Sands’ partner on Kenny’s retirement in 1862, and after Sands’ death in 1873 continued the Melbourne operations as Sands & McDougall, a company noted as stationers, booksellers and printers, and especially for their annual directory. This was published from 1863 as Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and Suburban Directory and from 1902 as Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne, Suburban and Country Directory, also incorporating Canberra 1940-47, and retitled Directory of Victoria from 1948. Ceasing with the 1974 volume in the ‘One hundred and seventeenth year of publication’, the directory had appeared annually since 1857 with the exception only of the single volume for the war years 1944-45.

Sands & McDougall appears to have employed door-to-door canvassers to check residents and businesses, blanks and vacancies in listings suggesting that visitors did not rely on hearsay but checked their information carefully. While researchers will find gaps and conflicts in the information, judicious and persistent cross-referencing of the street, alphabetical and trade sections usually produces dividends. There is simply nothing to match these directories for their reliability, comprehensive coverage, and continuity of publication. Though the Sands & McDougall directories may be supplemented by official Victorian post office directories, published between 1868 and 1885 by F.F. Bailliere, and between 1891 and 1892 and 1916, first by Wise, Caffin & Co. and later by H. Wise & Co., and which include Melbourne and suburbs, these are not annual publications, and the occupational and trade information is sparse. There are also various business directories, which proliferated after 1945.

SOURCE

Directories

https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00470b.htm

NEWSPAPER COVERAGE 1850s

how to interpret the biases of various papers and why p36 The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1851-1861 by Geoffrey Serle, 1977 Melbourne University Press.

MAPS

1837 robert russell map shewing the site of melb

‘Map shewing the site of Melbourne : and the position of the huts & buildings previous to the foundation of the township by Sir Richard Bourke in 1837’ / surveyed & drawn by Robert Russell ; Day & Haghe, lithrs. to the Queen

Creator: Russell, Robert, 1808-1900

Call Number MAP RM 1288 (Copy 1)

Created/Published [London] : Day & Haghe, [1837?] Extent 1 map : mounted on linen ; 47.5 x 64.5 cm.

national library of australia

https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/3602851

AND

Further reading

Rex Harcourt’s enormously interesting book “Southern Invasion, Northern Conquest” (Golden Point Press, 2001).

Richard Broome, Aboriginal Victorians: A history since 1800, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005

Contact history is covered by Richard Broome, Aboriginal

Australians (date) and Michael Christie, Aborigines in Colonial

Victoria (1997). A.G.L. Shaw’s account of the early Port Phillip

District (1997) covers inter-racial relations and early patterns of

immigration. The story of John Batman’s treaty is the subject of

Bain Attwood (with Helen Doyle), Possession: Batman’s treaty and

the matter of history (2009).

The theme of shaping the urban landscape incorporates planning and

architectural history. For the former, see Robert Freestone,

Designing Australian Cities (2007), and for the latter, see Philip

Goad, Melbourne Architecture (1999)

cemetaries:

Marjorie Morgan’s book, “The Old Melbourne Cemetery 1837 – 1922” published by the Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies in 1982, has names of people buried there from transcriptions of legible headstones made by G. P. Townend in 1913-14.

Isaac Selby wrote a book called “Old Pioneers Memorial History of Melbourne” in 1924 which extensively outines the history of persons connected to the cemetery.

Royal Historical Society of Victoria’s Historical Magazine, Volume 9, No. 1, pages 40-47 has an article on the cemetery.

Another book, “Melbourne Markets 1841-1979, the story of the fruit and vegetable markets in the City of Melbourne” (Footscray, 1980), edited by Colin E. Cole has material on Melbourne markets.

SOURCE

https://melbournewalks.com.au/the-old-melbourne-cemetery-queen-victoria-market-tour/

from fb

The US standard railroad gauge (distance between the rails) is 4 feet, 8.5 inches. That’s an exceedingly odd number. Why was that gauge used? Well, because that’s the way they built them in England, and English engineers designed the first US railroads. Why did the English build them like that? Because the first rail lines were built by the same people who built the wagon tramways, and that’s the gauge they used. So, why did ‘they’ use that gauge then? Because the people who built the tramways used the same jigs and tools that they had used for building wagons, which used that same wheel spacing. Why did the wagons have that particular odd wheel spacing? Well, if they tried to use any other spacing, the wagon wheels would break more often on some of the old, long distance roads in England . You see, that’s the spacing of the wheel ruts. So who built those old rutted roads? Imperial Rome built the first long distance roads in Europe (including England ) for their legions. Those roads have been used ever since. And what about the ruts in the roads? Roman war chariots formed the initial ruts, which everyone else had to match or run the risk of destroying their wagon wheels. Since the chariots were made for Imperial Rome , they were all alike in the matter of wheel spacing. Therefore the United States standard railroad gauge of 4 feet, 8.5 inches is derived from the original specifications for an Imperial Roman war chariot. Bureaucracies live forever. So the next time you are handed a specification/procedure/process and wonder ‘What horse’s as came up with this?’, you may be exactly right. Imperial Roman army chariots were made just wide enough to accommodate the rear ends of two war horses. (Two horses’ ases.) Now, the twist to the story: When you see a Space Shuttle sitting on its launch pad, there are two big booster rockets attached to the sides of the main fuel tank. These are solid rocket boosters, or SRBs. The SRBs are made by Thiokol at their factory in Utah . The engineers who designed the SRBs would have preferred to make them a bit fatter, but the SRBs had to be shipped by train from the factory to the launch site. The railroad line from the factory happens to run through 1a tunnel in the mountains, and the SRBs had to fit through that tunnel. The tunnel is slightly wider than the railroad track, and the railroad track, as you now know, is about as wide as two horses’ behinds. So, a major Space Shuttle design feature, of what is arguably the world’s most advanced transportation system, was determined over two thousand years ago by the width of a horse’s as. And you thought being a horse’s as wasn’t important? Ancient horse’s as*es control almost everything2.

hlkjlj;hliuytutyryyyy