BLOCK 50

approximate site

LETTSOM RAID see 1840 on timeline.

51

FAWKNERS HOTEL BLOCK 51 current site 419-429 Collins Street

-J.P. Fawkner opened Fawkner’s Hotel in a single-storey timber and brick building on the south-eastern corner of Collins and Market streets. This was leased to become the first home of the Melbourne Club in 1839. SOURCE ‘HOTELS’ DAVID DUNSTAN https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00727b.htm

-this was licensed and traded as SHAKESPEAR HOTEL then run under PASSMORE then became UNION CLUB

Union Club Hotel, corner of Collins & Market Streets, Melbourne

American & Australasian Photographic Companyc 1870-1875 ON 4/Box 63/no. 533 SOURCE https://search.sl.nsw.gov.au/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=ADLIB110041471&context=L&vid=SLNSW&search_scope=MOH&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US

THE SHAKESPEARE HOTEL. JOHN FAWKNER’S CORNER. By A. W. GREIG. Argus, Saturday 30 April 1927, page 10 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/385181

The projected rebuilding of the south-eastern corner of Collins and Market streets, where the Union Club Hotel is being demolished, has aroused interest in the somewhat confused traditions of the

spot. The Shakespeare hotel, which once

stood on this corner, is referred to as one of the oldest licensed houses in Melbourne. Even 50 years ago it was but a memory.

Chance has placed in my way a relic of this old hotel, in the form of a bill tendered by its landlord to some early day visitor.

Nearly 90 years ago, at the second sale of Crown lands in Melbourne, on Novem-ber 1, 1837, John Pascoe Fawkner bought this corner for the trifling sum of £10. Two years earlier he had erected a hotel some-where at the back of the present Customs building, near the site of the offices of the Electricity Commission; but on the laying out of the town this ground was reserved for Government use, and he knew that sooner or later he would have to give up possession. He accordingly took steps to transfer his business to the site of which he had acquired the legal freehold, and about the end of June, 1838, he moved into a building which he had erected on the Market street frontage, somewhere about the spot now occupied by the Colonial Mutual Buildings. For this he obtained a licence under the name of “Fawkner’s Hotel,” and in a shed at the back he estab-

lished the printing plant with which the

“Port Phillip Patriot” was produced. On the Collins street corner he seems to have had a timber-yard, for we find him adver- tising in April, 1839, “Van Diemen’s Land sawn timber, shingles, and laths” for sale; but he was already contemplating retire-ment to rural life, and after having held his licence lor 12 months he relinquished it. About the same time he was building on the Collins street corner of his block what was to be the first permanent home of the Melbourne Club, formed in the closing months of 1838; and in June, 1839, tenders were called for “fitting up the bal-

cony on the east and south fronts of the Melbourne Club House.”

For the foregoing account of the earliest history of Fawkner’s corner I have been compelled to rely more on inference, coupled with oral tradition, than on exact records. Historical topography for this stage of Melbourne’s existence is a diffi- cult study. From the time when the Mel-

bourne Club entered into occupation of its building, however, we are on firmer ground. Early in 1845 the club was looking forward to a move farther along Collins street, and Fawkner was advertising its premises as being to let from the following Septem-ber. He found a prospective tenant in the person of one Joseph Gregg, a former employee of the Melbourne Steam Naviga-tion Company, who on October 18, 1845, made application to the bench of magis-trates for a publican’s licence, handing in “a recommendation both numer-

ously and respectably signed,” as a

testimonial of his character. “There is at the present time,” the “Patriot” asserted, “a great want of an hotel in the town as the headquarters of captains and mates of vessels, whose whereabouts by that means would be more clearly defined.”

But the magistrates declined to issue a new licence until the annual licensing day came round, and Gregg turned his attention else-where, procuring the transfer of the Queen’s Head Hotel in Queen street, early in December. For some months longer the old clubhouse remained unused, but on May 2, 1846, a licence for it was granted to M. J. Davies, a former pilot from New castle, “on the understanding that it was to be considered as a family hotel.” Thus did the Shakespeare Hotel come into exist-ence, though why a hard-bitten old sailor should have chosen such a name for a tavern which was expected to become the resort of seafaring men is difficult to under-

stand. Perhaps Fawkner, who had early tried to make his own hotel a centre of culture by providing a library for the use of his lodgers, was the sponsor.

Mr. Davies remained in occupation of the Shakespeare for less than 12 months, for on February 9, 1847, he transferred his

licence to Joseph Cowell Passmore, who

had first entered the hotel business in Octo-ber, 1845, when he took over the Devonshire Arms, Collingwood, from Francis Clark. In those days magistrates demanded reasons from the principals concerned when a hotel

changed hands. Passmore was by trade a house painter, “and labouring under ill

health . . . . wished to obtain some more healthy employment,” while Clark, if I remember correctly, desired to devote more time to conducting a butchering business in which he was interested. It was in Pass- more’s time that the account to which I have already referred was rendered to some

lodger at the Shaklespeare. It has an ornate heading, engraved by Thomas Ham, exhibiting a bust of the poet, with flow-ing curls and upward turned moustache. For four days’ accommodation the charge is £1/12/4, but this includes more than £1 for liquid refreshments, and only 12/ for meals and beds. What make the document

more interesting are the pencilled notes on the back, representing tallies of sheep, &c., indicating that the customer to whom the

bill was rendered was a squatter, or at least the manager of a sheep station. Mr. W. A. Bon, of Bonnie Doon, who has pre-served this relic of the past, ascribes its date to the early fifties “anterior to the gold rush,” and in this he is probably right, for in 1851 or early in 1852 Passmore sold out from the Shakespeare, and moved down to the busier haunts of Elizabeth street, then becoming the high road to the gold-fields. Indeed, the Shakespeare seems to have stood on a quiet corner, although it was hard by the market, opened first in 1841,

and not far from the police office and its adjoining stocks. The stocks, it is true were beginning to fall into disrepute when the hotel was opened, and in 1849 the police

office was moved down to Swanston street. By this time, however, the Shakespeare had become one of the stopping places of the ‘buses which plied to St. Kilda and Brighton, making one trip a day to Brigh- ton, and two to St. Kilda, and charging repectively 1/ and 2/ a passenger. But generally we hear little of the Shakespeare in the ‘forties, and we can only conclude that it was carried on as its first licensee had promised it should be, as a quiet, well-conducted family hotel.

The original building, of which, with its high-peaked roof we get distant, unsatis- factory glimpses in some of the old pictures of the period, seems to have been pulled down some time in 1862, for about the end of this year we find the Shakespeare ad-vertised as a “newly built hotel.” The building then erected was presumably the one now disappearing. In 1864 or 1865 it became the home of the Union Club, and the Shakespeare Hotel passed out of exist-ence. The club only lasted for four or five years, and the building again fell vacant, but from 1870 onwards it was known as the Union Club Hotel.

SOURCEL: THE SHAKESPEARE HOTEL. JOHN FAWKNER’S CORNER. By A. W. GREIG. Argus, Saturday 30 April 1927, page 10 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/385181

Union Club

UNION CLUB The third attempt (in 1865) to set up a club to supplement the Melbourne Club saw a club for merchants, which leased the Shakespeare Hotel on the corner of Collins and Market streets in the business end of the city. Its rules differed from those of the Melbourne: strangers living more than 10 miles (16 km) from the General Post Office could be entertained to lunch or dinner. Pre-eminently a luncheon club, it was described as a morgue at night. Over-spending on redecoration and costs associated with honouring the lease led to its winding up in 1868, despite its nominal support among Melbourne’s mercantile establishment.

SOURCE UNION CLUB PAUL DE SERVILLE https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01529b.htm

THE UNION CLUB BLOCK 51 built on site of Shakespear Inn

The Union Club, at the corner of Market st, built on the site of Fawkners Shakespeare Inn, has given place to the AMP offices. For some years it was kept by Thomas Asche – father of Oscar, of theatrical fame – a tall, handsome, bearded Norwegian, who might have served a sculptor as model for a Viking, and who, were rumour to be believed, must have had a constitution in keeping with that of those hardy Norse rovers, for he was credited with consuming two bottles of brandy a day.

The house was much patronised, and an habitue was Alfred Tennyson Dickens. I see him now, with frock coat and top hat, nonchalantly leaning on the bar, listening to the barmaid, reminding one of George du Maurier’s superb illustration of Trilby’s father.

-SOURCE Melbourne inns that have gone BY MICK ROBERTS on https://timegents.com

/2018/08/09/melbourne-inns-that-have-gone/

The Bloodied Wombat’s Melbourne (FB) rtndoeSposr1i 78e1014F01gfbt211ufum6a4i5g86c222yh868,r aum4m

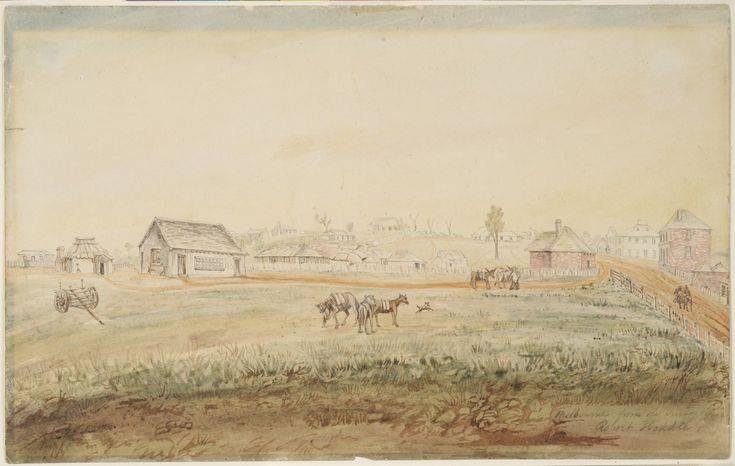

‘Melbourne from the Survey Office’, Robert Hoddle, 1840

Looking east along Collins St, with William St in foreground in this 1840 watercolour by the city’s famous surveyor-general.

The white building on the R far side of Market St is the first Melbourne Club, built 1839 on the site of a timberyard owned by John Pascoe Fawkner, later known as Shakespeare Hotel, demolished 1862 for Union Club Hotel. The first rudimentary Western Market would appear far R in 1841. SLV

https://bit.ly/3qcEZmt

———-

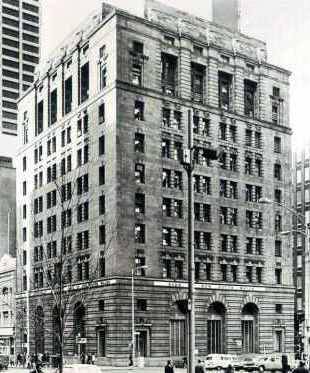

SOURCE: ‘Former Australian Mutual Provident Society Headquarters’ Other Name Bank of NSW Location 419-429 Collins Street,, MELBOURNE VIC Former AMP headquarters http://vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au/

search/nattrust_result_detail/64683

‘One of the finest examples of the 1920s Renaissance revival commercial palazzo in Australia built in 1929-31 in the financial heart of Melbourne as the Victorian headquarters for the Australian Mutual Provident Society, which had been founded originally in Sydney in 1849. Though opened in 1931 in a time of economic depression, this impressively decorated structure of advanced building technology well reflects the role of the AMP as a contemporary strong and stimulating financial force – characteristic of the Society’s history. The ten-storey building designed by architects Bates Smart and McCutcheon was built to the maximum allowable height limit of 132 feet. Framed in steel and clad with sawn Sydney freestone and Casterton granite, the former AMP Society Building is a period exemplar of the influence in Australia of contemporary American high-rise office building design of the 1920s.

Styled in a mannered interpretation of the Italian Renaissance, the building is an excellent example of masonry veneer construction with outstanding and original details and an elaborate sculptural relief by sculptor, Orlando H Dutton over the main entrance on Collins Street. Two unique features of the building are the concealed panel heating system, the first of its kind in Australia, and the adjustable steel slatted sunblinds on the Collins Street and Market Street upper floor windows. The impressive ground floor chamber, free of columns and with an elaborate coffered ceiling, is a rare and intact commercial interior of the 1920s decorated in a classically derived manner. Other interior elements of period significance include the first floor timber panelled boardroom with its elaborate marble fireplace surround and timepiece, adjacent panelled vestibule and bathroom with substantially intact period sanitary fittings. Also the wire lift cage and surrounding stairwell complete with scalloped light fittings at the rear of the banking chamber. This conservatively styled building won the fourth Royal Victorian Institute of Architects Street Architecture Medal in 1932.

Classified: 21/07/1988

————————————————

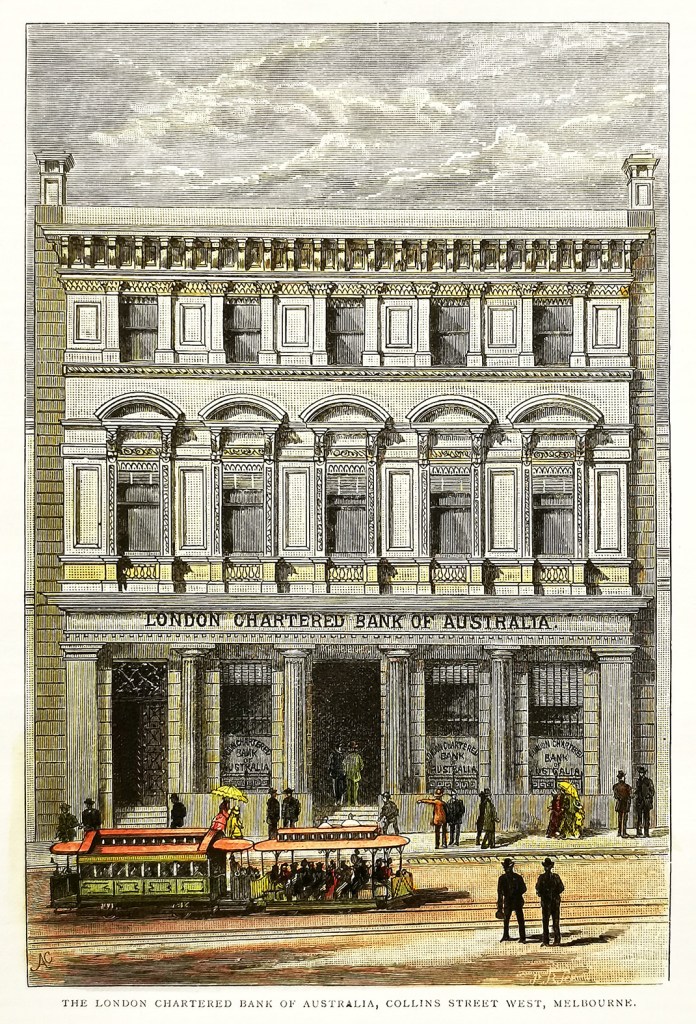

The London Chartered Bank of Australia, The current site 401-403 Collins St BLOCK 51

C1887 The London Chartered Bank of Australia, Collins Street West, Melbourne. by Albert Charles Cooke (1836 – 1902) source https://antiqueprintmaproom.com/product/the-london-chartered-bank-of-australia-collins-st-albert-charles-cooke/

……………………………….

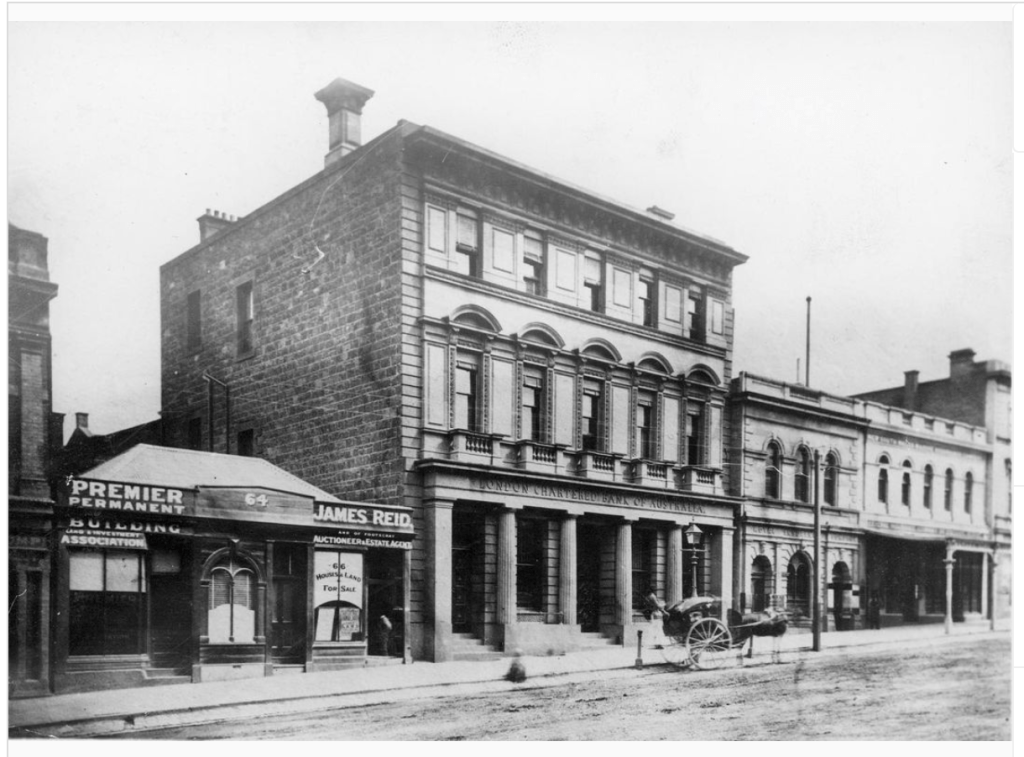

SOURCE The sale of the Collins street premises of the old London Bank From herald sun retro on instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/heraldsunphoto_retro/p/B7h-i5-gdLe/

This photo would be from 1865 onwards not the first building on same site.

and:

The sale of the Collins street premises of the old London Bank – formerly the London Chartered Bank of Australia will evoke many regretful memories in the minds of those whose vision is not limited merely to a successful monetary transaction.

The London Chartered Bank of Australia, founded in London in 1852, just 71 years ago – opened its doors in Melbourne and Sydney on July 1, 1853, and in Geelong on November 13 of the same year.

The Collins street bank was built about 1865 by Perry and Oakden, and was regarded as one of the finest pieces of architecture in Collins street. The lower story is Grecian Doric similar to the Theseum on the Acropolic at Athens and the upper stories are Italian Renaissance, the whole executed in solid bluestone, fit to last, as its founders had hoped, for centuries. Owing to the great expense of working bluestone, and also to the fact that stoneworkers who can handle this material are not so numerous as they once were, it is very unlikely that another such ornate bluestone building as the old bank will be erected in Melbourne.

Architects admire both the Doric and the Renaissance treatment of the building, but they admire the styles separately rather than as a whole, for the mixture of styles 1,500 years apart does not appeal altogether to the architectural sense. The interior, and especially the banking chamber, always receives unreserved commendation. There are larger chambers, but there are none that give a greater impression of dignity. One architect describes the cedar and mahogany fittings as “wonderful”.

The London Bank was recently sold to the English, Scottish, and Australian Bank, and it was afterwards purchased by Mr. T. M. Burke for $60,000. It will be used as the headquarters of his business, so it is satisfactory to know that one of Melbourne’s historic buildings will be preserved. [The Argus, 1923]

Undated image

.

*Collins Street had two sets of numbers, east and west of Elizabeth Street. James Reid, to the left of the bank building in the photograph is no.64 Collins Street West.

The London Bank would become 401-403 Collins St.

By 1937 the building had been demolished.

SOURCE The sale of the Collins street premises of the old London Bank From herald sun retro on instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/heraldsunphoto_retro/p/B7h-i5-gdLe/

52

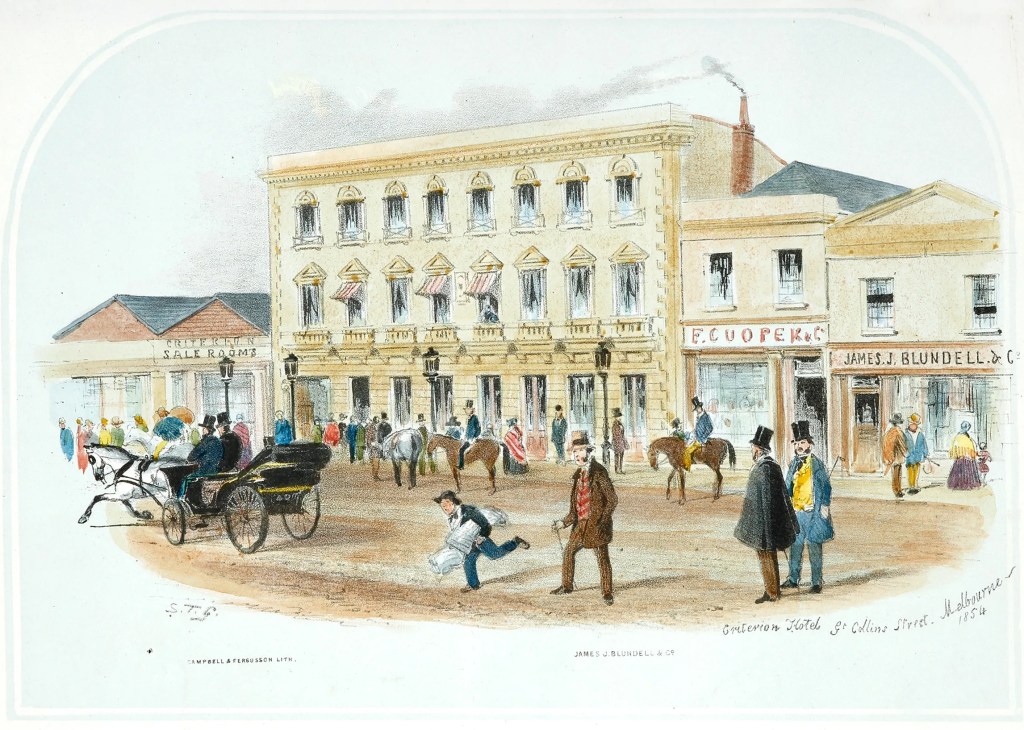

CRITERION HOTEL 1853 BLOCK 52

Americans Samuel Moss and Charles Wedel renovated the Criterion on the south side of Collins, between Elizabeth and Queen streets. In 1853 they built a three-storey frontage and 28 bedrooms with bars, dining-rooms, billiard saloon, bath-house, hairdresser, bowling saloon and a vaudeville theatre to the rear. The bridal suite had amber satin sheets. SOURCE ‘HOTELS’ DAVID DUNSTAN https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00727b.htm

Criterion Hotel, Gt Collins Street, Melbourne, 1854 by Samuel Thomas Gill (1818 – 1880) SOURCE

https://antiqueprintmaproom.com/product/criterion-hotel-gt-collins-street-melbourne-185-samuel-thomas-gill/

CRITERION HOTEL BLOCK 52 ‘The flamboyant and successful Train, who imported ice from Boston and took the lead in organising a volunteer fire brigade, was the best known {as enterprising american influential figure}. Moss’s Criterion Hotel, the American head-quarters, lived up to its name’. -American influence in melbourne. SOURCE p124 The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1851-1861 by Geoffrey Serle, 1977 Melbourne University Press.

–

The Criterion, formerly on the present site of the Union Bank’s head office, was the most popular resort in the gold era, and was much patronised by the numerous American colony. Tradition has it that cocktails first made their appearance in its bar, the enterprising licensee having brought bartenders from California to concoct those mysterious compounds, which bear a somewhat similar relationship to good liquor that sausages do to prime meat.

SOURCE Melbourne inns that have gone BY MICK ROBERTS on https://timegents.com

/2018/08/09/melbourne-inns-that-have-gone/

BLOCK 53

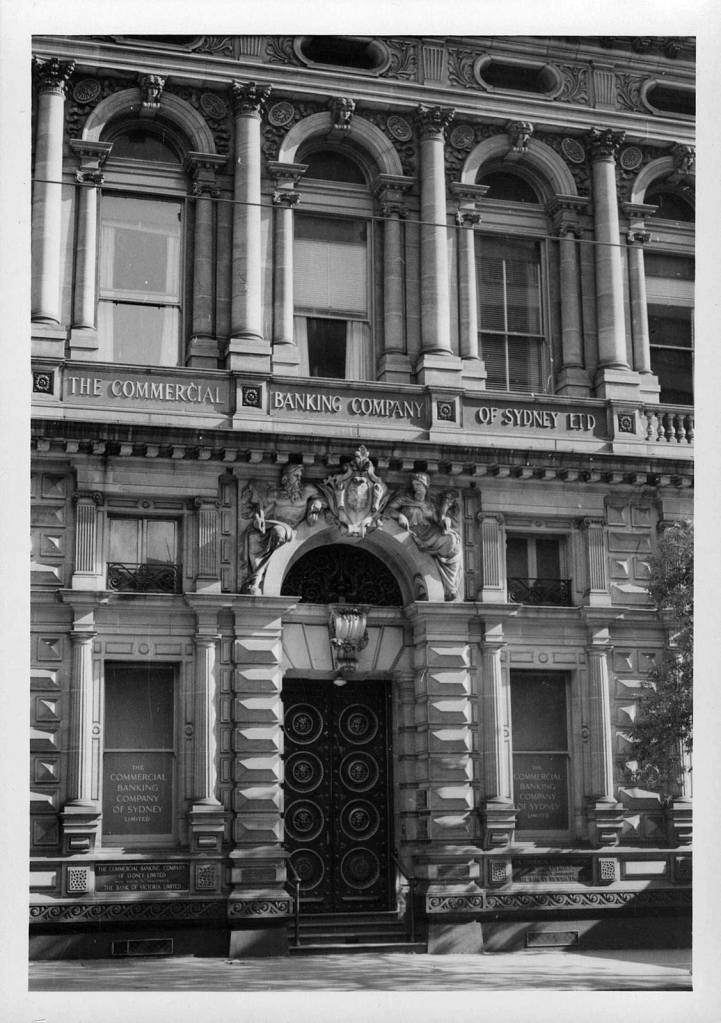

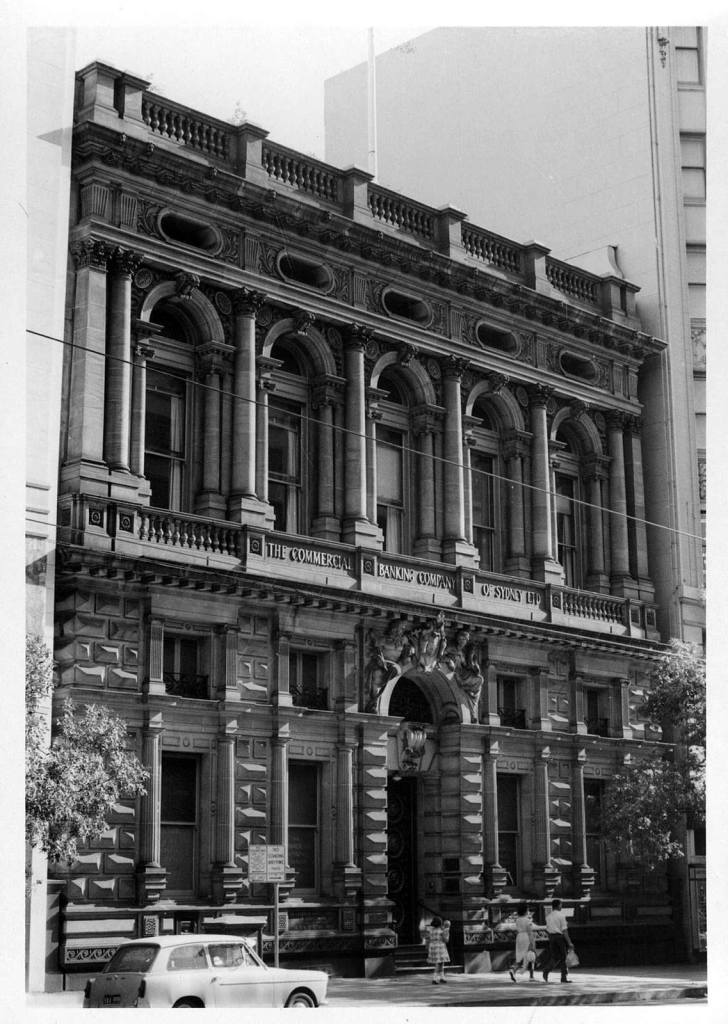

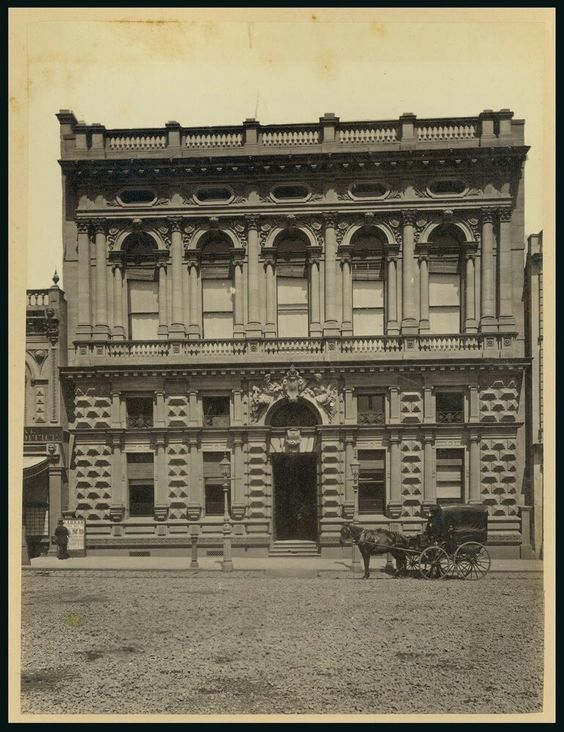

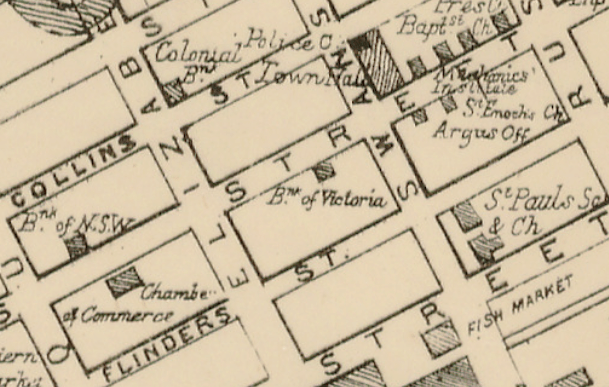

BANK OF VICTORIA aka VICTORIA BANK

Bank of Victoria current site 251 Collins Street, Melbourne ‘One of a series of banking houses built in Collins Street in the decades immediately after the gold rush. Situated on the south side of Collins Street, between Elizabeth and Swanston Streets, it had an ornate facade, with rustication of its stone on its lower level that gave the building a solid and heavy looking base. At the time this photograph was taken, in the mid-twentieth century, it was the Melbourne office of the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney (CBC Bank), which amalgamated with the Bank of Victoria in 1927. Sadly, this beautiful building was demolished around 1970, when the CBC Bank rebuilt its Melbourne office. It was a sad loss to the architecture of Collins Street.

Photographer: J T Collins

Source: State Library of Victoria Picture Collection’

SOURCE: from FB https://www.facebook.com/100045427796115/posts/3402582103160991/

Peter Andrew Barrett – Architectural and Urban Historian, Writer & Curator

see also:

citation: “Mammoth Nuggets of Australian Gold.” Illustrated London News, 29 Oct. 1853, p. 372. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, link-gale-com.ezproxy.slv.vic.gov.au/apps/doc/HN3100034990/ILN?u=slv&sid=bookmark-ILN&xid=e9ca938f. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

-downloaded as PDF.

also this pic:

‘Bank of Victoria on Collins St, Melbourne in Victoria in 1880. State Library of Victoria’

BANK OF VICTORIA

one pound note – 1893 to 1910:

and

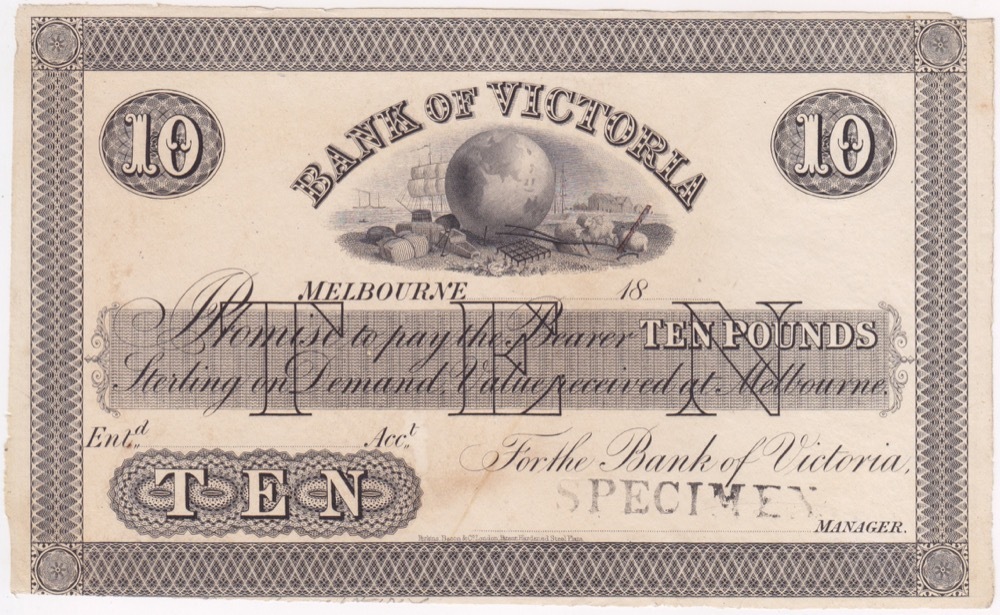

Bank Of Victoria (Melbourne) Ca 1853 10 Pounds Unissued Printer’s Proof MVR# 1 About Unc SOURCE STERLING AND CURRENCY

https://www.sterlingcurrency.com.au/bank-of-victoria-melbourne-ca-1853-10-pounds-uniss

and here it is: Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne directory mapAuthor / CreatorSands & McDougall Limited.Date1871?] from slv

see also A Century of Service: The Concise History of Victoria Bank & Trust Company by Johnson, Laurence S.Published by Victoria Bank & Trust Company, Victoria, TX, 1979

Block 54

1898 to 1920s: dentist and surgeon JJ Forster ran at 11 Swanston Street opp cathedral

Between 1890s and 1930s Around a thousand human teeth have been found – an intriguing legacy of the business that dentist and surgeon JJ Forster ran at 11 Swanston Street from 1898. Many teeth show obvious signs of decay, often with root exposure, meaning their bearers would have suffered excruciating pain prior to removal. JJ Forster’s trade in extractions was evidently flourishing – but success was not without its pitfalls. He was the target of a high-profile blackmail case in 1909 when letters were sent demanding £50 under threat of death “by bullet or bomb”. The threat was traced by police to a 16-year-old boy, who planned to use the cash to buy a film projector and tour the country screening movies.

The land at 11 Swanston Street, Melbourne, was purchased by John Batman at the first Melbourne land sales in 1837, and became one of the area’s earliest sites of European settlement. It was developed by Batman and used for various activities, including Melbourne’s first girls’ school, until John James Forster opened his dental practice in 1898. He practised there, next to the Prince’s Bridge Hotel (Young and Jackson’s) and opposite St Paul’s Cathedral, until his retirement in the 1920s. The premises was then taken on by dentists F & G Turner (his nephews, Frederick Charles Turner and George Harper Forster Turner), whose advertisement is pictured here.

https://medicalhistorymuseum.mdhs.unimelb.edu.au/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/dentistry-innovation-and-education

old ad from paper:

The Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 – 1954) Tue 5 Feb 1924 Page 3 Advertising

Actual teeth have been found in excavations

–there are photos but try and get better ones. From metro archeology

Pamphlet

BLOCK 54 cont

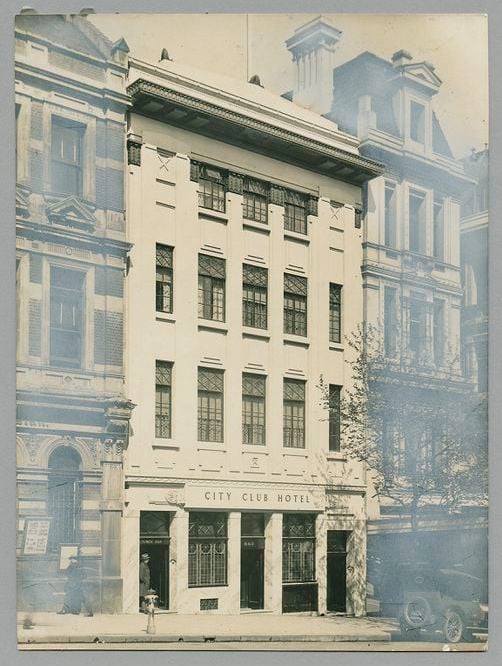

CITY CLUB HOTEL 209 Collins Street BLOCK 54

This building, erected in 1923-24, replaced an earlier City Club Hotel that had occupied this site from the late-nineteenth century. The hotel’s clientele in the 1920s was described as ‘a charmed circle’ that was the resort of artists, doctors, men of finance, and journalists. The hotel’s location next to the Argus newspaper office may explain it being a haunt of journalists.

The new City Club Hotel was designed by the architect J J Waldron of the architectural firm of Sydney Smith, Ogg and Serpell. As well as its entrances in Collins Street, the hotel was accessed from Queens Walk, an arcade that extended in an L-shape between Swanston and Collins streets. Upstairs in the City Club Hotel was a dining room that could seat up to 100 patrons, and hotel rooms. Remodelling works in the 1930s further improved and enlarged the hotel’s facilities.

Like many other buildings in this part of Collins Street, the City Club Hotel was purchased in the 1960s by the City of Melbourne, and was demolished to make way for the City Square. One building that was spared from demolition was the Regent Theatre (1929), situated further east in Collins Street from the City Club Hotel.

Photographer: Sutcliffe Pty Ltd

Source of Photograph: Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences Australia

source: City Club Hotel 209 Collins Street, Melbourne

Peter Andrew Barrett – Architectural and Urban Historian, Writer & Curator

eprnStoosda09b43eie710St2c37e r49lgp6 fi2um2at7671,6m76a61ll ·

great illustration here: of 1923 building

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1999733

- The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957) View title info

- Thu 6 Sep 1923

- Page 7

- NEW CITY CLUB HOTEL.

block 55

56

BLOCK 57 PHOTO photo taken late 1855 by Walter Woodbury showing Batman’s Hill taken from what is the present Collins St extension of docklands from then west melb gasworks chimney. ‘…this grainy image showing the corner of Spencer and Flinders streets. BLOCK 57 If one squints, you not only see the first Princes Bridge, but also Queens Wharf (which stretched between Spencer St and the current Aquarium site). Further to the right are the abattoirs that lined the Yarra, slowly polluting it with foul animal remains and noxious chemicals. At the bottom of the photo is the muddy flat of the nearby Melbourne Swamp, which was located north-west of Melbourne until drainage started in the 1870s. Then, in-between all of this, is Batman’s Hill. It is hard to believe for many Melburnians today, but the west side of Spencer St was originally an 18-metre hillock covered in she-oak, that sloped towards the Yarra. It was there that the city’s founder, John Batman, had his house. If one focuses right of centre of the hill, you can see the house standing on top, barricaded by a picket fence. When Batman died in 1839, it became a Government Office, and was later used as a hospital.’ SOURCE A view to a hill (with an explosive secret) 29th July, 2020 By Ashley Smith https://www.docklandsnews.com.au/ history_16633/ Langlands Iron Foundry 556−560 Flinders Street BLOCK 57 Langlands Iron Foundry 556−560 Flinders Street BLOCK 57 EST 1842 current site 556−560 Flinders Street ..the location of Victoria’s first iron foundry, which operated between 1842−1864 and represents the earliest known European occupation of this site. In subsequent years, the site was occupied by a shipping butcher (1864−1930s, lot 558/560), a bank (1876−1920, lot 556) and several other twentieth century commercial enterprises. source SOURCE ‘Preliminary results of excavations at Langlands Iron Foundry and Stooke’s Shipping Butchers, 556−560 Flinders Street, Melbourne Tom Mallett, Sarah Myers, Sarah Mirams, Felicity Coleman and Fiona Shanahan’ p1 then referred to as 139 Flinders Street, SOURCE ‘Preliminary results of excavations at Langlands Iron Foundry and Stooke’s Shipping Butchers, 556−560 Flinders Street, Melbourne Tom Mallett, Sarah Myers, Sarah Mirams, Felicity Coleman and Fiona Shanahan’ p2 Discussion and conclusion 556−560 Flinders Street represents only a small portion of the former Langlands Iron Foundry grounds. Preliminary results of the archaeological program suggest that the study area probably functioned as an outdoor yard space, with the major features comprising a brick-paved surface and well. There was also extensive evidence for the dumping of waste foundry products onsite, both during the foundry occupation, and just prior to the construction of new buildings on the premises in 1864 and 1876…. A broader archaeological assessment of the city block bound by Flinders Street, Flinders Lane, King Street and Spencer Street is required to assess the potential for intact foundry-related deposits and features. SOURCE ‘Preliminary results of excavations at Langlands Iron Foundry and Stooke’s Shipping Butchers, 556−560 Flinders Street, Melbourne Tom Mallett, Sarah Myers, Sarah Mirams, Felicity Coleman and Fiona Shanahan’ p89, 90 ALSO SEE::: PROV database::: Myers, Sarah, Sarah Mirams, and Tom Mallett. “Langlands Iron Foundry, Flinders Street, Melbourne.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22, no. 1 (2018): 78–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45154387. >>and in 1853: and ‘In the face of the glut of cheap imports, there was little scope for ambitious manufacturers except in fields where ‘natural protection’ applied {ie protected by tarifs?}. Thus the building industry, a few coachmakers, and brewers and other beverage-makers prospered. Cheap tallow made profitable manufacture of soap and candles possible; a few saddlers and tanners did well; so did Henry Langland’s and Thomas Fulton’s two iron foundaries whose products – casting for buildings, ornamental iron-work, agricultural implements and mining machinery – sold well despite competing imports and the lack of local raw material.’ SOURCE p.125 The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1851-1861 by Geoffrey Serle, 1977 Melbourne University Press. |

block 58

Lettsom Raid – Collins Street (approximate site)

In 1839, the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate started operations. Chief Protector George Robinson focused efforts in Melbourne, trying to break-up the Aboriginal camps by the Birrarung (Yarra River), and discouraging Aboriginal people from entering the town.

In 1840, there was a mass arrest and jailing of Aboriginal people in and around Melbourne. The so-called Lettsom Raid resulted in between 200 and 400 Aboriginal people being detained in barracks near the Birrarung (Yarra River). During the raid Winberri, a Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung man, was shot dead. Although only 23 years old, he was considered a remarkable young man ‘famous, respected and admired … Winberri was by family connection able to pass safely through distant remote tribes, a man with a “noble spirit” according to [William] Thomas, who wrote a three-page description of the unusual mourning ritual for Winberri carried out morning and evening by his aged father and his only sister‘ (Fels, 2011, p. 114).

Supposedly carried out in retaliation for frontier violence, the Lettsom Raid has been characterised as part of coercive actions, aimed to control Aboriginal people and exclude them from Melbourne (Standfield, 2011, p. 179).

source: https://aboriginal-map.melbourne.vic.gov.au/112

Block 59

John Fawkner’s residence, 424 Flinders Street, Melbourne

Derrimut, an important Yalukit-willam clan head (Bunurong Boon Wurrung), used diplomacy and established relationships with significant people in the colony as part of seeking to secure the rights to land for Bunurong Boon Wurrung and to uphold notions of mutual obligation.

Along with Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung clan head (ngurungaeta) Billibellary, Derrimut warned Fawkner that an attack was going to be made on him by other Eastern Kulin people. Derrimut associated closely with Fawkner and sometimes lived at Fawkner’s residence as part of the household.

source https://aboriginal-map.melbourne.vic.gov.au/106

FAWKNER’S HOUSE BLOCK 59

The first house built in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia by J.P. Faulkner [i.e. Fawkner] Esqr. [picture] / W.F. Evelyn Liardet pinxt

Creator

Liardet, W. F. E. (Wilbraham Frederick Evelyn), 1799-1878

Call Number

PIC Drawer 22 #R95

Created/Published

1836

Extent

1 watercolour ; 15.4 x 24 cm.

Physical Context

PIC Drawer 22 #R95-The first house built in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia by J.P. Faulkner [i.e. Fawkner] Esqr. [picture]

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-134635895/view

Fawkner’s House…1837 you can see it on Russell’s map so BLOCK 59

Melbourne From The Falls by Robert Russell, 1844. I think this is looking to block 59 or block 59-60 Source: State Library of Victoria

BLOCK 59

Three customs buildings have occupied the current site of the Old Customs House, culminating in the existing grand structure. Archaeological digs have revealed the foundations of the earlier buildings, and a detailed restoration project has returned the Customs House to its former glory.

Three Customs Houses

1841 Building

-bluestone Customs House with a slate roof was completed on this site in 1841.

-Designed by the Government architect in Sydney, it was Melbourne’s first stone building.

-It sat by the Turning Basin, a natural pool on the Yarra River that was the highest point to which ships could navigate up the river.

-Convicts were used to row the customs officers out to ships moored in the bay. Although the settlement was not a penal colony, several hundred convicts worked as servants or on government duties.

-by the 1850s critics called it one of the ‘ugliest and most inconvenient of all our public buildings’.

SOURCE

https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/customs-house/

1855 new building for custom house, is in use by 1858, but never really completed until 1876 to a newer design

Construction of the building commenced in 1855, but halted in 1858 when the economy slowed and government revenue declined.

With the vast increase in revenue brought by the gold rush, the Victorian Government commissioned immigrant architect Peter Kerr to design a new Customs House. Although the building was occupied by Customs in 1858, a shortage of funds prevented its completion.

Completion of a redesigned building recommenced in 1873, to a new design by Kerr and two other government architects, John James Clark and Arthur Ebden Johnson. The final 1876 building incorporated the Long Room from the 1850s building.

1876 design

The building was finally completed in 1876, to a modified design by Kerr and two other government architects.

SOURCE

https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/customs-house/

BLOCK 59 CONT

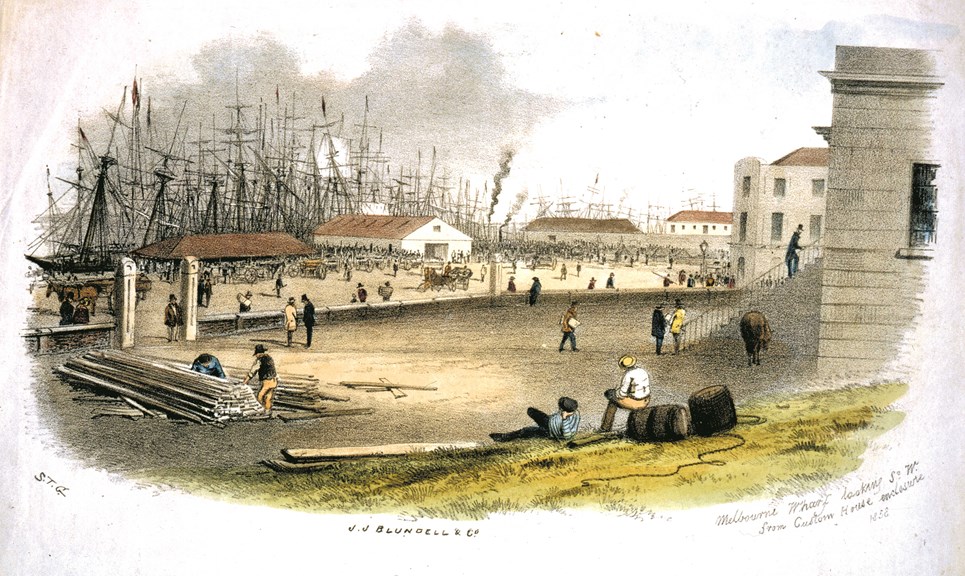

Customs House enclosure, Melbourne, 1858 looking on to SOUTH 3

SOURCE

https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/customs-house/

CUSTOMS HOUSE BLOCK 59

RAG FAIR at Customs House

‘Many of the migrants had to spend their small capitol within a few days and arrived on the goldfields penniless. Prevailing prices were bad enough, but there were other unexpected shocks. Few of the early migrants knew that Bank of England notes were not legal tender in the colony and could be cashed only at one-fifth discount. Many who had had to pay exorbitant sums for the transport of their luggage to town believed they had been swindled by the shipping companies, and advised their friends in letters home to make sure their tickets were made out to the ‘wharf at Melbourne’ on the river. The worst problem of all was what to do with luggage. Many had brought all their household chattells and could not afford to have much landed, as storage-space was so limited and expensive. The mattresses and bedding they threw overboard littered the beaches for years to come. Others began to sell what they could, sitting near the wharf pathetically offering watches, clothes, guns, pistols, books and furniture. This gathering in front of Customs House became known as ‘Rag Fair’ and developed into a popular market as regular traders moved in. -p67 The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1851-1861 by Geoffrey Serle, 1977 Melbourne University Press.