| BLOCK 40 |

BLOCK 40

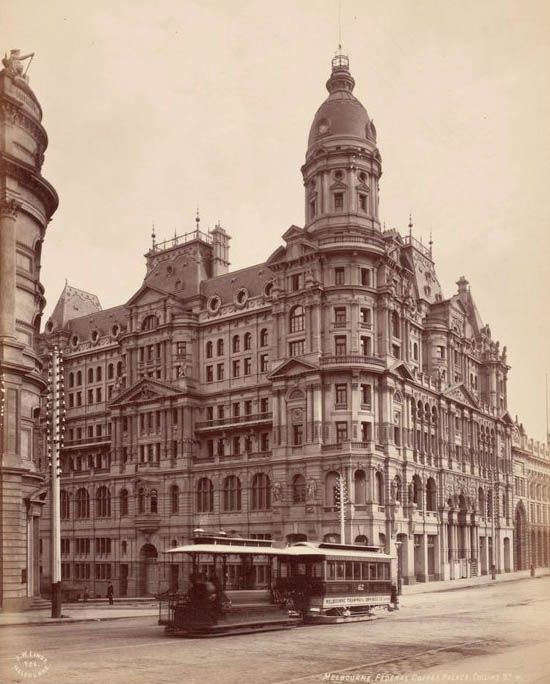

GRAND HOTEL >GRAND COFFEE PALACE>GRAND HOTEL>WINDSOR HOTEL

111 Spring Street BLOCK 40

Grand Hotel est 1883>1886

Grand Coffee Palace 1886>1897

Grand Hotel 1897>1923

The Windsor

In 1883, shipping magnate George Nipper built his magnificent dream, then known as The Grand Hotel. It was designed by famous architect Charles Webb, and was soon recognised as the most stylish and luxurious accommodation in Melbourne. SOURCE https://www.thehotelwindsor.com.au/about

The Honourable James Munro acquired the property in 1886. In association with the Honourable James Balfour MLC, Munro embarked on a massive expansion project that doubled the size of the hotel and saw the addition of the Grand Ballroom, the Grand Staircase, and twin cupola-capped towers. Visitors to the towers enjoyed views over Williamstown, the You Yangs, Mount Macedon, and the Dandenong Ranges. The original 200 rooms grew to 360, and The Grand Hotel boasted the latest amenities and five star conveniences: hot and cold water, electric lights, electric bells, and elevators.

At this time, the Temperance Party’s teetotal ideals had achieved a considerable following. Munro is famous for his flamboyant gesture of setting alight the hotel liquor license with the statement: “Well, gentlemen, this is what I think of the license”. And so the property became known as The Grand Coffee Palace.

This change did not prove successful, however. Just 10 years later, in 1897, the liquor license was reinstated, and the name The Grand Hotel was restored.

With its close proximity to Parliament House and Melbourne’s government offices, The Grand Hotel rapidly became associated with politics and politicians. So convenient was this relationship that in February and March 1898, the Drafting Committee for the Federal Constitution worked out the document’s final details from a suite within the hotel.

In the 1920s, a new company was incorporated. A group of investors, including Sir John Monash, purchased the property and began a major renovation. The Grand Ballroom’s unique high Victorian character, considered unfashionable at the time, was hidden, and would remain so for the next sixty years; leadlight windows at each end were replaced with clear glass, the ceiling domes that illuminated the room with natural light were concealed, and the richly patterned Victorian colour scheme was replaced with light pastels.

On 3 June 1923, with renovations complete, the hotel hosted a luncheon attended by His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales. In honour of this occasion, the hotel was appropriately renamed The Windsor.

SOURCE https://www.thehotelwindsor.com.au/about

Opposite the horse cab is the Grand Hotel. Built in the 1880s in the Renaissance Revival style, it was one of Melbourne’s grandest hotels. It epitomised the opulence of Marvellous Melbourne. Like London’s Ritz and Savoy and the Raffles in Singapore, the rich and famous stayed there. It oozed luxury. Soon after it was built it was expanded, its liquor licence was torn up and it was transformed into the Grand Coffee Palace, but this was not to last and, liquor licence restored, it reverted to the Grand Hotel in 1897. The year after (and the year before this photograph was taken), the Federal Constitution was drafted at the hotel. By then, the Grand was financially secure. It is still there, known now as the Windsor Hotel (renamed in 1920), dubbed by some the “Duchess of Spring St”.

SOURCE The grandeur of Spring St, early autumn 1899 Dr Cheryl Griffin | 23rd March, 2022 https://www.cbdnews.com.au/the-grandeur-of-spring-st-early-autumn-1899/

| BLOCK 41 ONE HALF OF GOVERNMENT BLOCK with OTHER HALF BEING BLOCK 33 see a-z 1836 this block is of a larger ‘government block’ an arm of NSW admin now that Melbourne is legitimised as as an extension of New South Wales >overall government block is bounded by Collins, Bourke, King and Spencer Streets ie between block 33 and 41. – for more details & sources see timeline. 1837 [Police] ‘Barracks’ and ‘Commissioners Store‘ are shown on 1837 map by Russell Robert Questions: was the ‘police barracks’ a gaol at all? What is in a commissioners store? gunpowder and magazines? wheat? |

| BLOCK 42 here |

| Block 43 MITRE TAVERN 5 Bank Place and LAMB INN > CLARENDON HOTEL >SCOTTS HOTEL 444 Collins St Shown as Clarendon hotel in 1865 map The Lamb Inn, Collins Street, 1875. Liardet, W. F. E. (Wilbraham Frederick Evelyn), 1799-1878. State Library of Victoria https://australianfoodtimeline.com.au /1837-9-melbournes-first-pubs -Well known was George Smith’s Lamb Inn in Collins Street west, ‘a series of low shingled weatherboard cottages joined together with dark passageways’ on a site purchased at the first land sale in 1837. ‘A roystering place for shepherds with cheques’ its large dining-room was used for meetings. Here sporting clubs and companies were founded, coroner’s inquests held and duels organised. Sold in 1840, the licence lapsed when the new owner went bankrupt. Reopened in 1849 as the Clarendon Family Hotel, it was rebuilt as Scott’s Hotel in 1861 and became a Melbourne institution. https://www.emelbourne.net.au /biogs/EM00727b.htm SEE also: The Lamb Inn, a “roystering place for shepherds with cheques”, c. 1840 by Dr Cheryl Griffin | 25th October, 2023, CBDNews.com.au https://www.cbdnews.com.au/the-lamb-inn-a-roystering-place-for-shepherds-with-cheques-c-1840 Address: Scotts Hotel was situated at 444 Collins St, built in 1860 and substantially remodelled in 1913-14 under a design by the architect, Arthur H Fisher. The site was first occupied by the Lamb Inn in 1837, renovated as the Clarendon Family Hotel in 1852 and then purchased by Edward Scott in 1860. Scotts Hotel was renowned for the pastoral property auctions held there, as the gathering place for racehorse owners and breeders, as the Melbourne residence of English cricketers like WG Grace and as Dame Nellie Melba’s favourite hotel. The prestige of the hotel had diminished by the mid-20th century and ceased trading in 1961 when the building was purchased by the Royal Insurance Company, ending its claim to be the oldest continuously licensed site in Victoria. Source: https://www.cbdnews.com.au/scotts-hotel-melbourne/ |

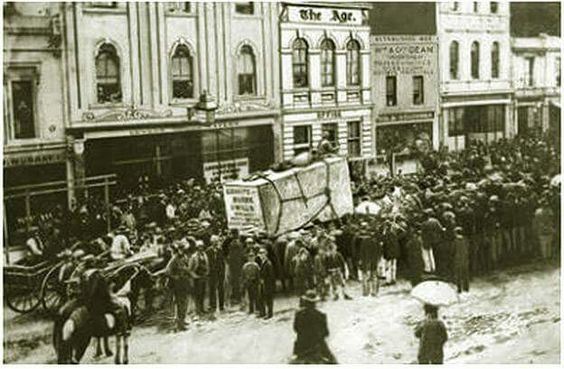

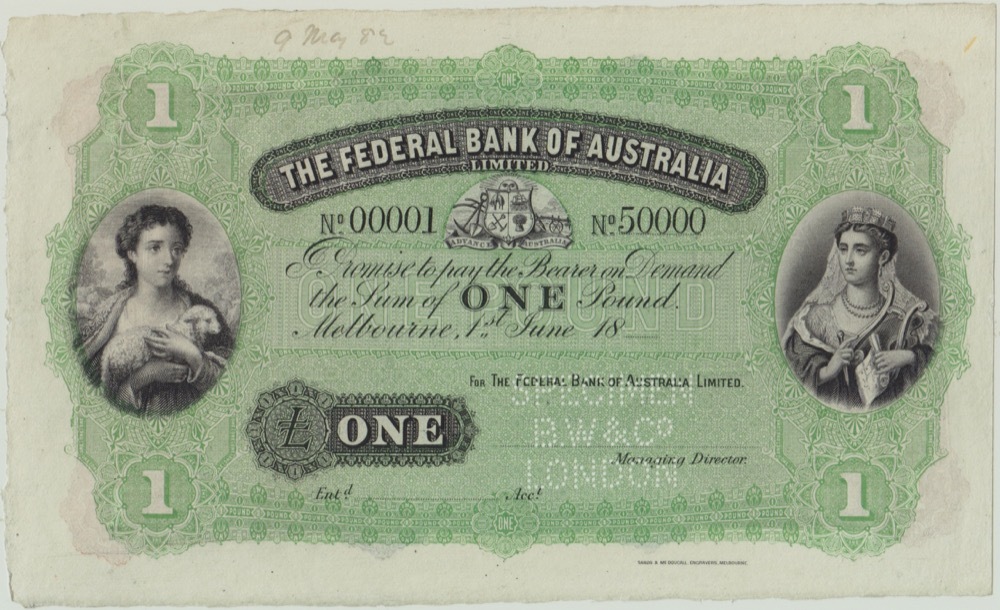

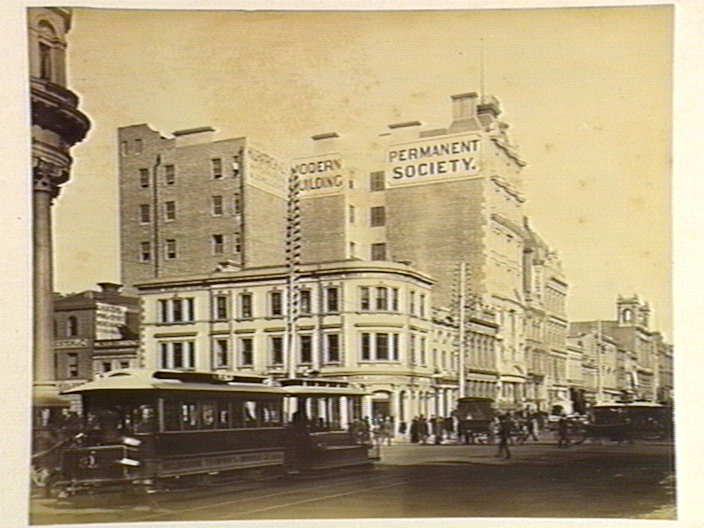

| BLOCK 44 The first building for THE AGE is previously UNION INN 1860: The Age is on west of Elizabeth St in what was originally a building called the Union Inn between Collins and Little Collins streets BLOCK 44 SOURCE for location: ‘About midway on the west side of the section of Elizabeth street between Collins and Little Collins streets stood in the early ‘fifties the Union Inn. This gave place in 1855 to the office of the “Age ‘ which had been established in the preceding year. Next door, on the south side, the London Tavern was opened in 1859’ SOURCE The Story of Elizabeth Street Once an “Unhealthy Hollow” By A. W. GREIG, Argus, Saturday 4 May 1935, page 5 also, uncited photo on pintrest locates The Age Newspaper Building at 67 Elizabeth St,Melbourne in Victoria (year unknown). and here’s the photo:  FEDERAL BANK OF AUSTRALIA BLOCK 44 The Federal Bank of Australia was established in Melbourne in 1881, and opened for business in April, 1882. Initially successful, the company expanded to New South Wales by absorbing the Sydney and Country Bank Limited in 1882. Banknotes were issued at branches in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide.[1] The headquarters was in a modest building on the corner of Elizabeth and Collins Street in Melbourne.[2] The managing director was the politician James Munro, who was Premier of Victoria in 1890-1892. He was also president on the Federal Building Society, established about the same time as the Federal Bank. Both institutions principally invested in speculative land companies, which boomed in the 1880s as the economy expanded, and property prices climbed to a frenzied peak in about 1890. The boom was followed by a crash, and the precipitous decline in property prices led to the collapse of building societies burdened by unsustainable debts, with the uncertainty soon spreading to banks.[3] A run by depositors in late 1892 forced the Federal to close its doors “temporarily” on 30 January 1893.[4][5] The doors never reopened, and the Federal became the first bank,[3] as opposed to building society, to fail as part of the Australian banking crisis of 1893. A provisional liquidator was appointed on 3 February 1893.[6] The extent of the bank’s debts, especially to English banks, was soon revealed.[7] James Munro, already in debt (much to his own companies), had resigned as Premier in early 1892, and left for the UK, but returned voluntarily, and was declared bankrupt in February 1893. His personal debts amounted to £97,000, and his companies owed over £600,000. –https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Federal_Bank_of_Australia  Federal Bank Of Australia (Melbourne) Ca 1882 1 Pound Unissued Specimen Note MVR# 1 Uncirculated Serials: 0001 – 50000 SOURCE: STERLING AND CURRENCY https://www.sterlingcurrency.com.au /federal-bank-of-australia-melbourne-ca-1882-1-poun  source [Collins Street West at Elizabeth Street showing Federal Bank of Australia and Modern Permanent Building Society] Date(s) of creation: [1888?] this is my definitive locator of address SOURCE https://www.slv.vic.gov.au /pictoria/gid/slv-pic-aab69443 |

Block 45 Ceremonial grounds

1837 Ceremony place – ‘on low ground between what are now Swanston and Elizabeth streets’

During the early colonial period, significant gatherings of the Eastern Kulin were held within the city.

For example, resident George Russell recalled a ‘corroboree’ in 1837 ‘on the low ground between what are now Swanston and Elizabeth streets’. He described about 300 Aboriginal people camped at this site. He noted a ‘large camp fire was made’ and 50–60 dancers performed, presenting a ‘striking and interesting’ scene. The women ‘acted as the musicians of the party’ and the young men and boys were ‘painted with white streaks for the occasion’ (Boon Wurrung Foundation, 2018). SOURCE: https://aboriginal-map.melbourne.vic.gov.au/94

1860 BLOCK 45

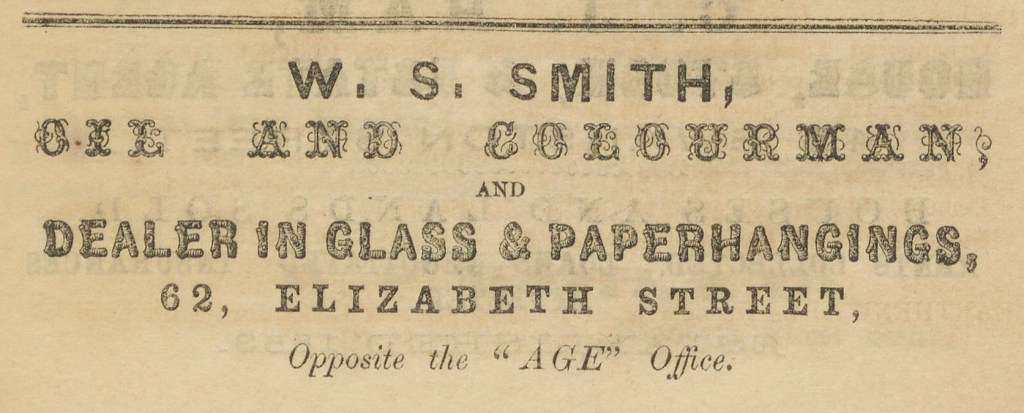

number 62 Elizabeth st (the east side of Elizabeth St) is opposite The Age between Collins and Little Collins. see below for how I figured this.

SOURCE ad from p.30 of Sands Kenny and Co street directory

so 1860 the east of Elizabeth St between Collins and Little Collins, contains street number 62 in BLOCK 45

Block 46 The Cavalier Tea Rooms

The Cavalier Tea Rooms were located in Queens Walk Arcade, the Victoria Buildings, 68 Swanston St., Melbourne, on the corner of Swanston and Collins Streets.

47

BLOCK 48

CRAIG, WILLIAMSON & THOMAS 57-67 Little Collins Street Melbourne BLOCK 48

SOURCE: HODDLE GRID HERITAGE REVIEW p976

SITE NAME Former Craig, Williamson Pty Ltd complex STREET ADDRESS 57-67 Little Collins Street Melbourne PROPERTY ID 105968 https://hdp-au-prod-app-com-participate-files.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/

6915/9494/5186/PROPERTY_105913_57TO67_LITTLE_COLLINS_ST.pdf

49

BLOCK 49

FEDERAL COFFEE PALACE current site 555 Collins St BLOCK 49

The Federal Coffee Palace was a large elaborate French Renaissance revival style 560 room temperance hotel built between 1886 and 1888 >stood until 1972 and 1973.[1] Located on Collins Street, on the corner of King Street, near Spencer Street Station (the address is now 555 Collins Street), SOURCE https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Federal_Coffee_Palace

A cable tram, apart of Melbourne’s early tram network, passes the ornate Victorian Gothic Federal Coffee Palace on the south-west corner of Collins and King Streets in the Melbourne city centre, dated approximately between 1890 to 1900. SOURCE https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Coffee_Palace#/media/File:A_tram_car_passes_the_Federal_Coffee_Palace_in_Melbourne,_Victoria,_Australia.jpg

With its opening planned to commemorate the centenary of the founding of Australia and the 1888 International Exhibition, the construction of the Federal Coffee Palace, one of the largest hotels in Australia, was perhaps the greatest monument to the temperance movement. Designed in the French Renaissance style, the façade was embellished with statues, griffins and Venus in a chariot drawn by four seahorses. The building was crowned with an iron-framed domed tower. New passenger elevators—first demonstrated at the Sydney Exhibition—allowed the building to soar to seven storeys. According to the Federal Coffee Palace Visitor’s Guide, which was presented to every visitor, there were three lifts for passengers and others for luggage. Bedrooms were located on the top five floors, while the stately ground and first floors contained majestic dining, lounge, sitting, smoking, writing, and billiard rooms. There were electric service bells, gaslights, and kitchens “fitted with the most approved inventions for aiding proficients [sic] in the culinary arts,” while the luxury brand Pears soap was used in the lavatories and bathrooms (16–17).

SOURCE Coffee Palaces in Australia: A Pub with No Beer https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.464 Noyce, D. C. (2012). Coffee Palaces in Australia: A Pub with No Beer. M/C Journal, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.464